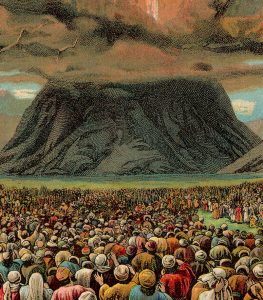

The Torah tells us in this week’s reading that we must always remember what happened at Sinai. “Just guard yourselves, and guard your souls very well, lest you forget the things that your eyes saw, lest it leave your heart all the days of your life. And you shall make it known to your children and grandchildren, the day that you stood before HaShem your G-d at Chorev” [Dev. 4:9-10].

The Torah tells us in this week’s reading that we must always remember what happened at Sinai. “Just guard yourselves, and guard your souls very well, lest you forget the things that your eyes saw, lest it leave your heart all the days of your life. And you shall make it known to your children and grandchildren, the day that you stood before HaShem your G-d at Chorev” [Dev. 4:9-10].

The Rambam [Maimonides] says (in his Igeres Teiman, his letter to Yemenite Jewry) that this isn’t simply something we believe, but the foundation of Jewish belief. But… isn’t that circular reasoning? How can something be its own foundation? It’s something we believe, therefore we believe it and everything else also. Right?

Actually, no, it’s not circular. Maimonides says that this is the foundation because every Jew knows that his or her own great-great-grandparents believed that his or her own great-great-(great-great-great etc.)-grandparents were there. As in, Jews have traditionally believed that their own forebears were actually at the foot of Mount Sinai and saw it happen.

Maimonides asserts that there is only one way for that belief to take root, and that by the same standards that we know most anything, we are able to analyze this event and reach the conclusion that we know it happened. It’s not just a belief, it’s knowledge.

Why is it so common to dismiss this as just another story? The answer is simple: because of the ramifications. Under most circumstances, no one would believe that a community of millions of people believe that their own ancestors witnessed an event, yet it’s all mythology. If Brazilians were holding an annual feast to commemorate a massive flood that nearly destroyed the community, the impartial observer would tend to believe that the flood must have actually happened — and that’s true even if the flood was reported to have taken place hundreds or even thousands of years ago. Because everyone knows that floods can happen, and it’s possible for communities to escape them by the narrowest of margins.

But knowing that this particular story may be difficult to believe, Maimonides points to this week’s reading: “when you will ask about the first days that happened before you, from the day G-d Created man on the earth and from one end of the heavens to the other, has this ever been, or has [a story] like this ever been heard — has a nation heard the Voice of G-d speaking from inside the fire, as you heard, and lived?” [4:32-33] The Torah says bluntly that, as Maimonides put it, “there never was such a thing before, and there will never be anything like it.”

This is an amazing prediction, especially considering how world history has played out over the past 3300 years. It’s not just that there are other religions, it’s that today over fifty percent of the world’s population derives their beliefs from our Bible. Today’s dominant religions begin here — that G-d revealed Himself to the Jewish Nation. And they all also believe that at some point, the Jews got it wrong.

All of them believe that they know the Jews got it wrong, because someone told them so. Either that someone was a prophet, or that someone was an angel, or that someone was even divinity in human form — but someone told them. No one believes that G-d publicly revealed Himself once again to say so. Today, there are more Americans who believe an angel talked to a man in a cave in upstate New York and showed him the new path, than there are Jews in the world who [try to] follow the rules laid out in the Torah!

What is it about this story, that no one tried to duplicate it? Doesn’t it make more sense to start a new religion by saying that G-d came back to tell us the new way? And for that matter… how did the Torah know and declare with full confidence that although the Jews came to believe the story as told in our Torah, no one would ever get a group of people to believe a new version of this story, ever again?

Maimonides may have been on to something.

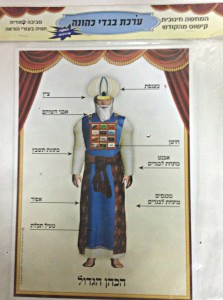

The Sifsei Chachamim points out that this is a unique moment. It was forbidden to leave the Temple Mount wearing those unique garments — so why was Aharon told to ascend the mountain in them, and Elazar to return wearing them?

The Sifsei Chachamim points out that this is a unique moment. It was forbidden to leave the Temple Mount wearing those unique garments — so why was Aharon told to ascend the mountain in them, and Elazar to return wearing them?

As the Rav of his shul, Rabbi Dovid Katz shlit”a, pointed out last night, Rav Hertzberg would also speak truth to power. He was fired from rabbinic posts for being too honest — until a group of devoted followers created a synagogue, named for his father Avraham zt”l, and set him up as their Rabbi.

As the Rav of his shul, Rabbi Dovid Katz shlit”a, pointed out last night, Rav Hertzberg would also speak truth to power. He was fired from rabbinic posts for being too honest — until a group of devoted followers created a synagogue, named for his father Avraham zt”l, and set him up as their Rabbi.