The first Mishnah asks: “From when do we read the Shema at night? From the time that the Kohanim enter to eat their Terumah.” [Brachos 1:1] This is a very complicated answer to a very straightforward question.

The Shema is a basic Jewish ritual, required in the Torah for men over the age of 13, as it says, “and you shall speak of them… when you lie down, and when you rise up” [Deut. 6:7]. Twice a day we recite the Shema, two [and, Rabbinically, a third] short readings from the Torah, accepting that G-d is our King and we are His servants.

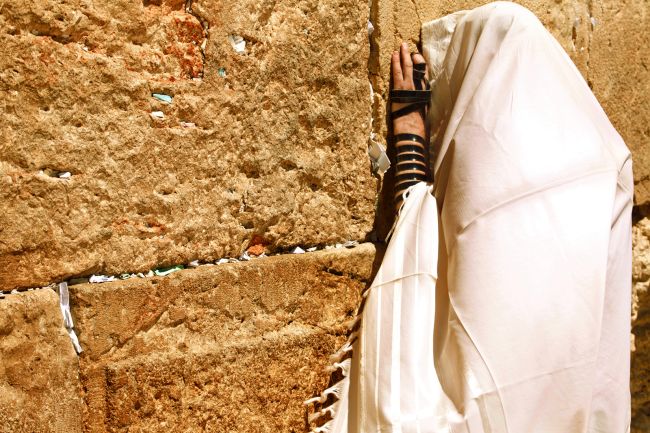

Terumah, on the other hand, requires much more explanation and understanding. The Kohanim, the Priests, descendants of Aharon, received the first of the crop in the Land of Israel as Terumah. It was a sanctified offering, to be eaten in a state of purity. A Kohen who contacted impurity had to go through a period and process of purification, which varied depending upon the severity of the impurity, and would have to immerse him or herself in a ritual bath. And then, as it says in our reading this week, “And the sun comes, and he is purified, and then he may eat from the Holy things” [Lev. 22:7].

The Talmud [Brachos 2a] asks, why add all of this complexity? The Kohanim are pure, able to eat their Terumah, after stars emerge at night. In Judaism, the evening begins the new day — as we read in the beginning of the Torah, “and it was evening and it was morning…” Once the stars come out, we know the new day has begun. So why not simply say so? The Mishnah should tell us that we read the Shema at night, after the stars come out!

The Sages answer that we are learning two lessons at once. In many cases of impurity, the Kohen had to bring an offering in the Holy Temple on the eighth day, having completed the purification process. Note that the verse in our parsha says “and the sun comes” — does that mean after the sun comes down, or after it comes up? One might imagine that it means after sunrise the following morning, when the Kohen brings his offering, and is fully purified. Perhaps he or she cannot eat Terumah until after bringing this offering.

By tying the Kohanim eating Terumah to the time for the Shema in the evening, the Mishnah clarifies that Kohanim may eat their Terumah at night, although they have not yet brought their offering that may only be done during the (following) day. And that is why the Mishnah gave such a complex answer — to tie the two together, indicating both that the Kohanim may begin eating Terumah at night, and also that one must recite the Shema after the stars come out.

After all of the foregoing, one might still wonder, is there no real connection between the two? In the end, all we learn is that the time for saying the Shema is the same moment that Kohanim are permitted to resume consuming Terumah.

The Iglei Tal says, in the name of his father, that the behavior of the Kohen teaches a lesson to all of us. The entire day this Kohen was impure, and even after he immersed in a ritual bath he was unable to eat Terumah. Now, simply because the sun has set, he may eat it once again.

This tells us that every evening is truly a new day. Saying the Shema, accepting G-d’s Kingdom, becomes a new obligation, as the Shema of the previous morning applied only to that previous day.

Our reading also discusses the holidays, including the period of Counting the Omer, the 49 days between the first days of Pesach (Passover) and Shavuos. Each of these 49 days, in Kabbalah, is tied to separate iterations of the seven mystical spheres — one for each day out of seven in each week, and one for each week out of the seven weeks of the Omer. Each combination of day and week, then, occurs only once per year.

This is another way of teaching us the same lesson: that each day is both a new opportunity and a new obligation. We must aim to set the past behind us, and grow anew, each and every day.